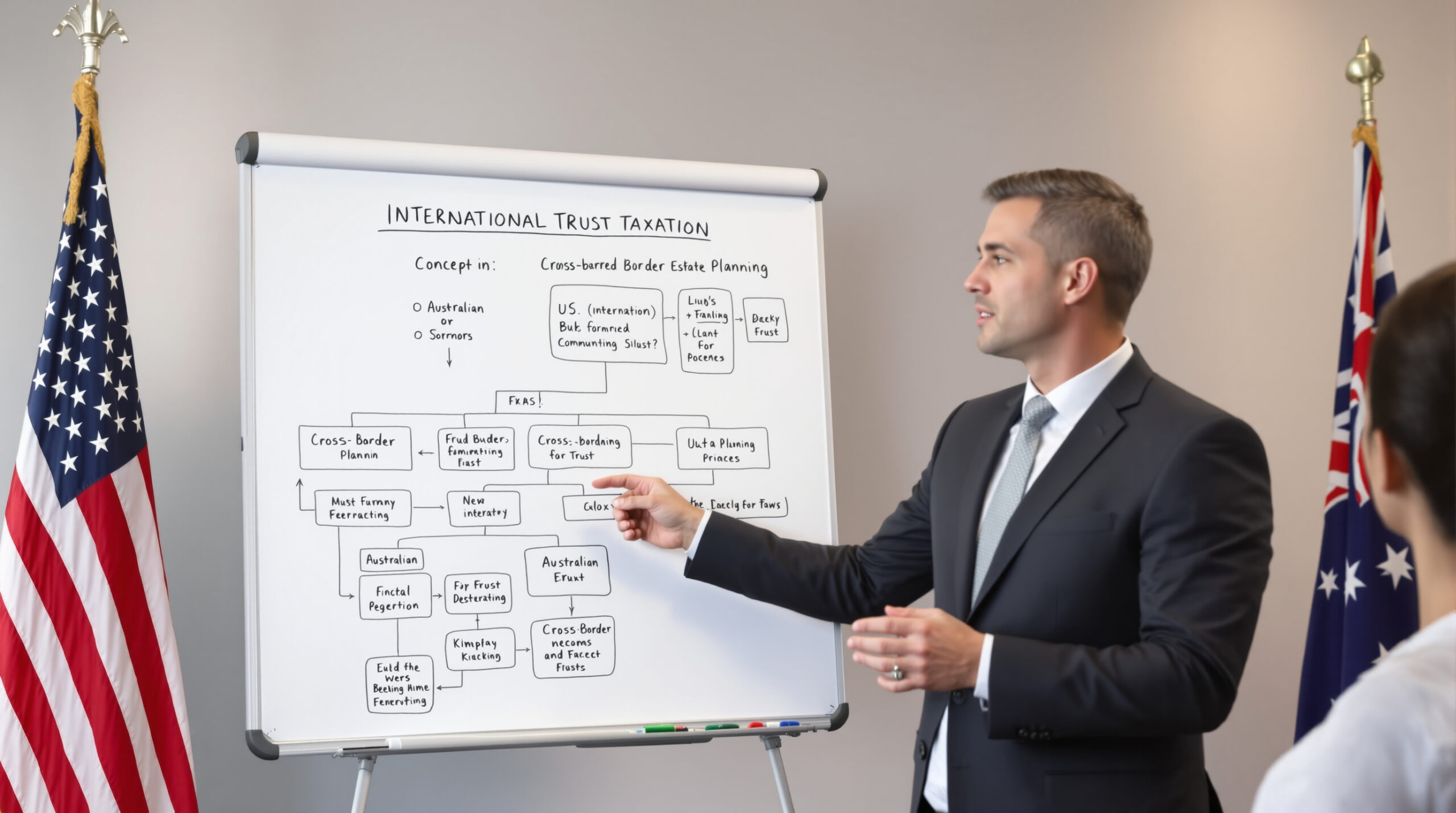

How Are Family Trusts Taxed in Australia for U.S. Citizens? The Cross-Border Misstep That Can Trigger Double Taxation and Six-Figure Losses

Most U.S. citizens with international family ties assume their overseas family trust is protected and tax-efficient—until the IRS and Australian Tax Office (ATO) both come calling. For 2025, an overlooked rule now leaves expats, dual citizens, and California high-net-worth families at risk of paying overlapping tax rates that can exceed 50% on the same trust income. In this post, I break down what every U.S. taxpayer with Australian connections must do to avoid massive penalties, double taxation, and irreversible compliance mistakes.

Understanding how are family trusts taxed in Australia begins with knowing that the ATO generally taxes beneficiaries, not the trust, except in special circumstances (like non-resident trusts or undistributed income). For U.S. citizens, that income remains taxable again in the U.S. under worldwide income rules. The only way to prevent double taxation is to align trust classification, residency, and timing of distributions so that foreign tax credits under IRS Form 1116 can offset ATO assessments rather than overlap them.

Quick Answer: If you’re a U.S. citizen with access to, distributions from, or control over an Australian family trust, you’re taxed by both the IRS and the ATO on worldwide income—even if the trust’s assets are offshore. The U.S. treats foreign trusts punitively, often requiring Form 3520/3520-A filings and imposing U.S. income tax on trust distributions, corpus returns, and sometimes on “phantom” income you never touch. Compliance failures trigger up to 35% penalties on distributions and $10,000+ late filing fines. See IRS instructions for Form 3520-A for details.

Section 1: The Real Tax Risk—How U.S. and Australian Tax Law Collide

If you’re a U.S. citizen in California, your worldwide income is taxed by the IRS no matter where you live or where your family trust is based. Australia taxes beneficiaries and sometimes the trust itself, depending on residency status and trust structure. It’s a collision course that trips up thousands of expats and dual citizens every year—often resulting in:

To truly grasp how are family trusts taxed in Australia, you must distinguish between discretionary and fixed trusts. In discretionary structures, trustees control income allocations each year, and the ATO taxes beneficiaries on amounts “presently entitled.” But when a U.S. person is a beneficiary, the IRS may treat the same flow as a foreign grantor or non-grantor trust—creating misaligned timing. Coordinating these classifications before distributions is key to avoiding mismatched tax events across jurisdictions.

- IRS taxing distributed income, retained earnings, and sometimes capital returns

- ATO taxing trust income based on residency status, sometimes regardless of distributions

- Reporting mismatches that trigger audits, penalties, and even double taxation (both ATO and IRS tax the same dollar)

For example: Sarah, a U.S. citizen in Los Angeles with a $500,000 beneficial interest in her parents’ Melbourne trust, receives $40,000 in distributions for the 2024–2025 tax year. The ATO taxes her as a non-resident beneficiary at top rates, and the IRS taxes the entire amount as foreign trust income. The result? Her combined effective tax rate approaches 55% after foreign tax credits and exclusion limits. Without pre-planning, she loses $22,000+ just by failing to align her reporting.

Understanding how are family trusts taxed in Australia is critical because the ATO looks through the trust to tax beneficiaries directly, while the IRS often treats the same trust as a separate foreign entity. This means the same dollar can be taxed twice—once under Division 6 of Australia’s ITAA 1936 and again under the U.S. grantor or non-grantor trust rules. Advanced planning, like establishing a parallel U.S. trust wrapper, helps align both tax systems and reduce the effective tax rate to as low as 28–32% instead of 50%+.

KDA Case Study: Real Estate Investor Navigates Dual Trust Taxation

Meet Peter, a real estate investor with dual citizenship (U.S. and Australia) based in Palo Alto.

Persona: Dual citizen, HNW, $2.3M assets in an Australian family trust; additional $1.1M in U.S. real estate and equities.

Problem: Peter received $65,000 in annual trust distributions from Australia to fund U.S. real estate investments. His CPA missed key U.S. reporting (Form 3520/3520-A), and the trust structure was ordinary under Australian law but classified as a grantor trust by the IRS. Peter faced a $32,500 (50%) IRS penalty plus $19,200 in double-taxation exposure.

KDA’s Strategy: We recalculated all required IRS filings, demonstrated “reasonable cause” for late Form 3520/3520-A, and structured a U.S. trust wrapper to absorb future distributions tax-effectively. We also claimed avoidable double-taxation through the Foreign Tax Credit (Form 1116) and performed meticulous residency analysis. Peter paid $4,500 in KDA fees. First year net tax savings: $38,900; three-year projected savings: $104,000. 8.6x ROI.

Ready to see how we can help you? Explore more success stories on our case studies page to discover proven strategies that have saved our clients thousands in taxes.

How Does the U.S. Tax an Australian Family Trust?

The IRS taxes foreign trusts under two main regimes:

- Grantor trust: Taxed as if the grantor (creator) directly owns the assets/income

- Non-grantor trust: Treated as a separate entity, distributions to U.S. persons are taxable as ordinary income, sometimes with additional “throwback” taxes on accumulated amounts

Regardless of Australian law, the IRS scrutinizes:

- Your status as a beneficiary, trustee, or grantor

- Receipt of distributions or loans from the trust

- Any control, power, or benefit from the trust (even if not exercised)

Filings required:

- Form 3520 (and 3520-A) for certain transactions or relationship to the trust

- FBAR (FinCEN 114) for foreign accounts with $10,000+ balance

- Form 8938 (FATCA) for specified foreign financial assets

Failure to file brings 35% penalties on distributions and $10,000 for late/incomplete forms (see IRS instructions). Most U.S. CPAs are not trained in cross-border trust reporting, putting clients at audit and penalty risk every year.

When Does Australia Tax a U.S. Citizen’s Trust Interest?

The ATO’s approach is based on residency, trust structure (“discretionary” vs. “fixed”), and source of income:

- If you’re a resident beneficiary, you’re taxed on worldwide trust income

- If non-resident (U.S. based), you pay tax on Australian-sourced trust income and some capital gains, at penal non-resident rates (up to 45%)

- Certain “taxable” distributions to U.S. citizens are taxed again (even if also taxed by the IRS)

Funds that are classified as corpus (original capital) may escape ATO tax, but U.S. rules may still tax corpus distributions as income, depending on historical recordkeeping and reporting sequence. This mismatch creates errors and year-over-year audit exposure.

Many taxpayers misunderstand how are family trusts taxed in Australia when distributions come from accumulated income versus capital. The ATO’s treatment depends on whether earnings were previously taxed in Australia, while the IRS looks at distribution character through the “throwback” rules for foreign trusts (IRC Sections 665–668). Without consistent tracking, even prior-year Australian income can become reclassified as taxable again in the U.S.—a costly duplication most advisors miss.

Why Most Accountants and Families Get This Wrong (and Pay Six Figures in Penalties)

The #1 mistake? Assuming only “income” distributions count for U.S. filing—and only Australian-sourced amounts count for ATO tax. Here’s where it blows up:

- Issue #1: IRS counts “loans,” “gifts,” and in some cases, perceived access (even if you did not receive a wire) as reportable (and taxable) trust events

- Issue #2: Both IRS and ATO treat many Australian family trusts as noncompliant by default, triggering extra scrutiny

- Issue #3: U.S. and Australian definitions of “income” and “beneficiary” do not align, so gaps in reporting (or double reporting) are common

Result? IRS penalty letters for 35% of any late-reported trust distribution, plus ATO penalty assessments if the funds are not taxed in Australia due to reporting gaps.

Red Flag Alert: IRS Form 3520 and 3520-A are not optional. Per IRS Publication 3520-A, every “foreign trust with a U.S. owner” must file, and failure to do so itself is a $10,000+ offense, even with no distributions made.

Pro Strategies: Reducing U.S.–Australia Trust Tax with Dual Compliance Moves

What can you do? Five concrete strategies:

- Classify your trust proactively for U.S. purposes—work with cross-border tax counsel to “grantor-proof” your estate structure

- Claim foreign tax credits for Australian taxes paid, using IRS Form 1116

- Optimize timing of distributions (bunch into low-tax years, coordinate with currency swings, use annual exclusion windows)

- Meticulously document trust corpus, contributions, and ownership to avoid IRS misclassification

- Early-file Form 3520/3520-A and never rely on “no distribution, no filing” logic

For a full overview of international trust compliance and legacy strategy, see our California Guide to Estate and Legacy Tax Planning.

Common Reader Questions About Australian Family Trust Taxation

Can I Just Ignore Small Trust Distributions?

No. The IRS has no de minimis threshold for trust reporting, and your banking activity may flag offshore wires over $10,000 regardless. Always file Forms 3520/3520-A for every year you receive a trust distribution, no matter how small.

Will the U.S. and ATO Communicate About My Family Trust?

Increasingly, yes. Under tax information exchange agreements, both countries share data related to trust distributions and accounts. Failing to report on both sides nearly guarantees an audit.

What Happens If I Miss an Australian Family Trust Filing?

Expect IRS late-file penalties starting at $10,000 per occurrence, 35% withholding on distributions, and potential criminal referral for willful neglect. In Australia, late or unresolved trust income cases often incur additional penalty rates.

Should I Use an Australian Accountant or U.S. Tax Advisor?

Both—but your U.S. advisor must understand Australian trust law, and vice versa. Most U.S. preparers are not trained in cross-border reporting for Australia, putting you at major risk.

Myth Bust: “If I Don’t Touch the Money, It’s Not Taxed”

This belief can cost hundreds of thousands. The IRS taxes undistributed earnings in some structures (“grantor” trusts), treats constructive benefit as income, and imposes penalties for any unreported trust interest even if you never received a wire transfer. Always clarify with a cross-border tax expert before assuming you are exempt from filing or tax.

Case Document Checklist for 2025 Tax Year Reporting

- Trust deed, schedule of beneficiaries, and historical accounting records

- Proof of foreign taxes paid (ATO notices)

- Wire receipts for U.S. inbound transfers

- Prior year Form 3520/3520-A filings

- U.S. passport and residency details

This information is current as of 10/20/2025. Tax laws change frequently. Verify updates with the IRS or ATO if reading this later.

Book a Dual Jurisdiction Tax Strategy Consultation

If you’re a U.S. citizen with Australian trust interests, don’t risk six-figure double taxation or IRS audit. Book your confidential consult and receive a detailed compliance road map for all your cross-border trust and legacy planning needs. Click here to book your consultation now.